Low-Temperature Control, Heat Rejection, and Thermal Stability Across Marine Plants

System Group: Cooling & Heat Transfer

Primary Role: Controlled removal of heat below ambient temperature for preservation, process stability, comfort, and equipment protection

Applies To: Merchant Ships · Offshore Platforms & Rigs · Superyachts · Naval & Special Vessels

Interfaces: Seawater Cooling · HT/LT Freshwater · Heat Exchangers · HVAC · Electrical Systems · Automation

Operational Criticality: Continuous (often non-redundant for mission or habitability)

Failure Consequence: Food loss → habitability failure → electronics trips → process shutdown → safety risk

Refrigeration is not “cold making”.

It is forced heat relocation against the natural gradient, and it is therefore one of the most energy-intensive and failure-sensitive systems onboard.

Contents

- System Purpose and Design Intent

- Refrigeration Fundamentals (Marine Context)

- Boundaries, Interfaces, and Separation Philosophy

- Refrigeration and Chilled Water Architecture Across Marine Sectors

4.1 Merchant Ships

4.2 Offshore Platforms and Rigs

4.3 Superyachts and High-Comfort Vessels - Major Refrigeration and Chilled Water Systems

5.1 Direct Expansion (DX) Refrigeration

5.2 Central Refrigeration Plants

5.3 Chilled Water Systems

5.4 Cascade and Low-Temperature Systems - Major Machinery and Components

6.1 Compressors

6.2 Condensers

6.3 Evaporators

6.4 Expansion Devices

6.5 Refrigerants and Oils

6.6 Controls, Sensors, and Safeties - Control Under Real Operating Conditions

- Fouling, Leakage, and Degradation Reality

- Human Oversight, Watchkeeping, and Engineering Judgement

- Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

1. System Purpose and Design Intent

Refrigeration and chilled water systems exist to maintain thermal conditions that cannot occur naturally onboard.

They protect:

- perishable stores

- pharmaceuticals and chemicals

- electronic equipment

- living spaces

- process streams offshore

Unlike cooling systems that merely reject heat, refrigeration systems must:

- extract heat from cold spaces

- compress and relocate it

- reject it at a higher temperature elsewhere

This makes them:

- power intensive

- control sensitive

- vulnerable to degradation

The design intent is continuous, predictable cold production, not peak performance.

2. Refrigeration Fundamentals (Marine Context)

Marine refrigeration is based on the vapour compression cycle:

- Heat is absorbed in the evaporator

- Refrigerant vapour is compressed

- Heat is rejected in the condenser

- Pressure is reduced through expansion

- The cycle repeats

This cycle operates under constraints unique to ships:

- variable seawater temperature

- vessel motion and vibration

- space and noise limitations

- intermittent load profiles

- limited redundancy

Refrigeration systems rarely fail suddenly.

They fail through loss of margin.

3. Boundaries, Interfaces, and Separation Philosophy

Refrigeration systems sit at critical interfaces:

- cold spaces ↔ machinery spaces

- electrical power ↔ thermal rejection

- freshwater ↔ seawater cooling

They must be isolated from:

- bilge contamination

- firemain systems

- uncontrolled drainage

Heat rejection usually occurs via:

- seawater-cooled condensers

- LT freshwater circuits feeding central coolers

Loss of separation leads to:

- refrigerant contamination

- condenser fouling

- rapid performance collapse

4. Refrigeration and Chilled Water Architecture Across Marine Sectors

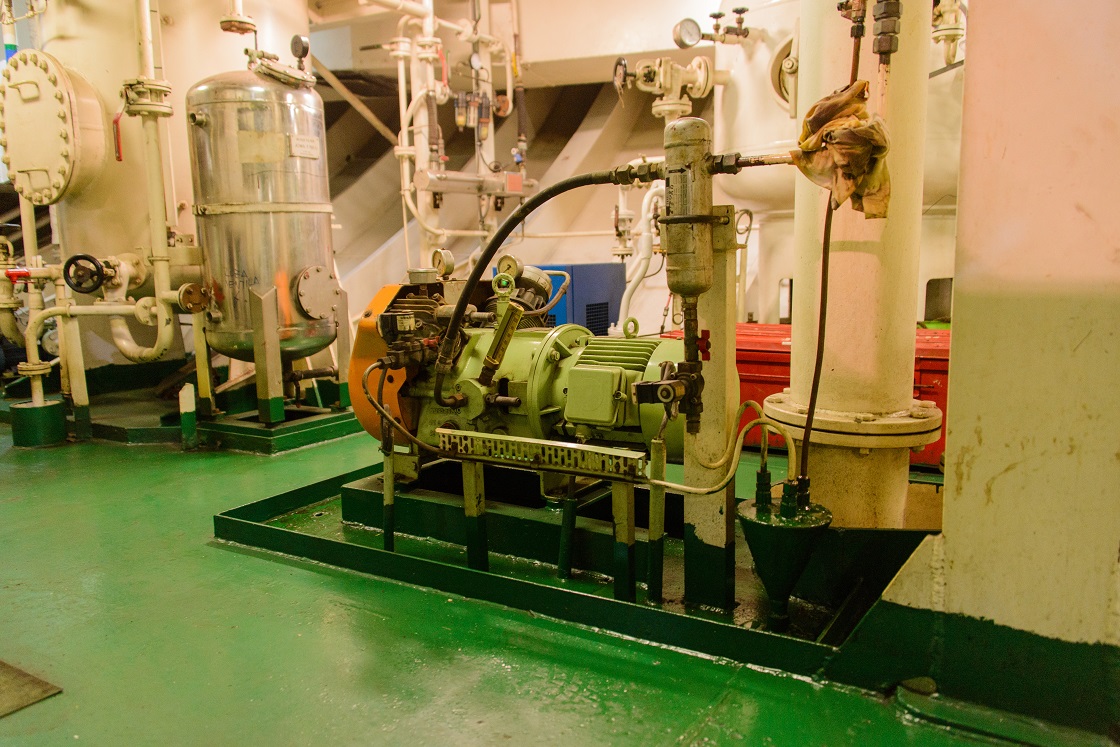

4.1 Merchant Ships

On merchant vessels, refrigeration serves:

- provision rooms

- reefer containers

- air-conditioning via chilled water

Systems are:

- robust

- energy conscious

- designed for minimal intervention

Failure impacts cargo, crew welfare, and compliance.

4.2 Offshore Platforms and Rigs

On offshore installations, refrigeration becomes process-critical.

Used for:

- gas dehydration

- hydrocarbon dew point control

- chemical storage

- HVAC for enclosed modules

Systems are:

- redundant

- continuously monitored

- tightly interlocked

Loss of refrigeration may force process shutdown.

4.3 Superyachts and High-Comfort Vessels

On superyachts, chilled water systems dominate.

They serve:

- zoned accommodation HVAC

- galleys and cold rooms

- wine cellars and specialty storage

- noise-isolated comfort cooling

Design priorities include:

- silence

- vibration isolation

- redundancy without visible machinery

Comfort systems may appear separate — but they rely on the same thermal foundations as industrial plants.

5. Major Refrigeration and Chilled Water Systems

5.1 Direct Expansion (DX) Refrigeration

DX systems cool spaces directly via refrigerant evaporation in local evaporators.

Advantages:

- simplicity

- high efficiency

Limitations:

- leak sensitivity

- limited distribution distance

- maintenance complexity in occupied spaces

5.2 Central Refrigeration Plants

Central plants use multiple compressors feeding several evaporators.

Advantages:

- redundancy

- easier maintenance

- consolidated control

They concentrate risk and demand disciplined monitoring.

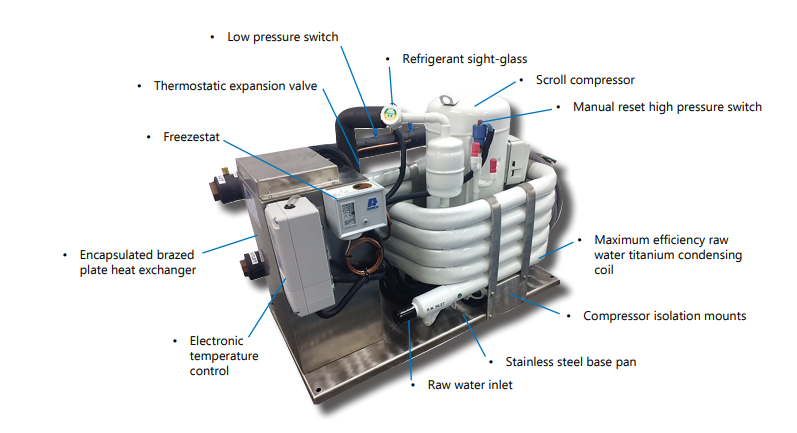

5.3 Chilled Water Systems

Chilled water systems decouple refrigeration from end users.

Refrigeration produces cold water, which is distributed to:

- air handling units

- fan coils

- process coolers

This architecture improves flexibility and comfort control at the cost of efficiency.

5.4 Cascade and Low-Temperature Systems

Used for:

- ultra-low temperature storage

- LNG-related processes

- specialty offshore applications

These systems use multiple refrigerants and stages, increasing complexity and failure sensitivity.

6. Major Machinery and Components

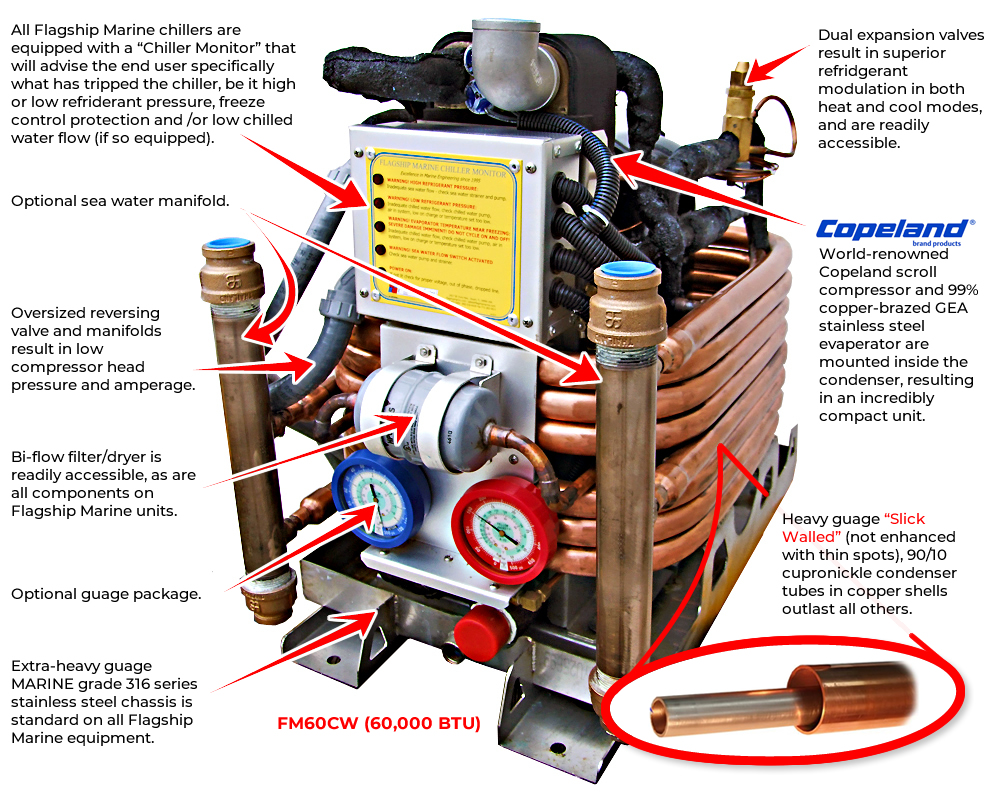

6.1 Compressors

Types include:

- reciprocating

- screw

- scroll

- centrifugal (large plants)

Compressors define:

- capacity

- efficiency

- vibration

- oil management complexity

They are the primary failure driver in refrigeration systems.

6.2 Condensers

Condensers reject heat to:

- seawater

- freshwater circuits

- air (limited use)

Fouling or scaling here raises discharge pressure and destroys efficiency long before alarms trigger.

6.3 Evaporators

Evaporators absorb heat from:

- air

- water

- process fluids

Ice formation, oil logging, and airflow restriction silently reduce capacity.

6.4 Expansion Devices

Expansion valves control refrigerant flow and evaporator pressure.

Poor control causes:

- hunting

- liquid carryover

- compressor damage

6.5 Refrigerants and Oils

Modern marine refrigerants are selected under:

- environmental regulation

- efficiency demands

- safety classification

Oil compatibility is critical. Oil migration is a common hidden failure mode.

6.6 Controls, Sensors, and Safeties

Refrigeration relies heavily on:

- pressure switches

- temperature sensors

- oil level controls

- safety cut-outs

Sensor drift leads to false confidence.

7. Control Under Real Operating Conditions

Marine refrigeration must cope with:

- varying ambient seawater temperature

- fluctuating electrical supply

- intermittent load

- fouled heat rejection surfaces

Systems compensate until margin disappears.

At that point, shutdowns become frequent and unexplained.

8. Fouling, Leakage, and Degradation Reality

Refrigeration systems degrade through:

- condenser fouling

- refrigerant leakage

- oil contamination

- control instability

Small leaks reduce capacity long before alarms detect them.

9. Human Oversight, Watchkeeping, and Engineering Judgement

Automation reports pressures and temperatures.

Engineers detect:

- rising compressor run time

- unstable suction pressure

- frequent defrost cycles

- unexplained power increase

Cold failure is usually preceded by behavioural changes, not alarms.

10. Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Refrigeration failure propagates into:

- HVAC collapse

- electrical overload

- food safety loss

- process shutdown offshore

Because refrigeration depends on every cooling system above it, it fails last — and recovers slowest.